The road to impact is slow and winding

If you're new here, welcome! You haven't missed much the last few weeks.

I had hoped to be able to deliver weekly posts when I began this project, only to need to prioritize a serious family health emergency. That was followed by a mountain of tasks related to wrapping up a job and preparing for a big move with family in tow I had, of course, fallen behind on. Everyone is healthy again, for which I am incredibly thankful. The to-do list has now shrunk, and I can deliver posts more regularly again. I'm grateful for this, too.

The last few months have been challenging in plenty of ways, but one was having to put away the illusion of control I like to maintain over both my personal and professional day-to-day. I know this control is an illusion, but find it a comforting and necessary one.

I loooove structure.

Outlier's newsroom has an abundance of structures we use before reporting even begins; from information needs assessments to a harm-matrix used to help decide which projects deserve resources to a discernment process for what goes into thrice-weekly newsletters. These tools help build the discipline needed to avoid falling prey to the temptation of agenda setting. These tools make it more likely we can execute an editorial strategy aligned to community needs.

But even with plenty of discipline and discernment, impact can be illusive.

Information is powerful. But does anybody in news really understand the mechanics of this power? Engineers understand how to harness water's energy to create electricity, and can then make this power available to turn on a light, for example. That's incredible, especially since combining electricity and water in the wrong way can literally cause death. And yet, the origins of hydroelectric power have been in the human knowledge bank since about 200 BC.

One would think comparatively easy to understand what it takes to discover, refine, produce and distribute information to improve conditions for individuals or groups experiencing harm. But no. The relationship between information and real impact eludes even algorithms.

This past weekend I was at the Reva & David Logan Symposium on Investigative Reporting this past weekend, where reporters and editors highlighted stories that managed to break through and create change. The lack of any pattern was what I found most noticeable.

This is not a call to try to figure out how to predict impact on the front end. That effort would run counter to prioritizing reporting to can fill info and accountability gaps, which requires consistent effort and focus on need-not outcome. Still, I did feel called to think more deeply about the words, "actionable" and "valuable" which I've often used to describe reporting I aspire to do.

One recording and two days

Two reporting projects challenged me to expand my thinking. The first was a reference to ProPublica reporting by Ginger Thompson on the family separation policy of President Donald Trump's first term. The story is only 16 grafs long, and mostly describes an audio clip of children screaming and crying for their mothers and fathers after being separated from them and detained inside a U.S. Customs and Border patrol facility. That story ran on June 18, 2018. The outcry was immediate and widespread. Trump signed an executive order two days later walking the policy back. Not content with the incredibly swift and broad impact, Thompson kept reporting, and found some separations were still happening months later. How lucky are we to have Ginger Thompson in this world and this work? Very.

Two things about this reporting and its impact that feel important in thinking about the nexus between information that can be valuable, actionable, and impactful.

First, there is no nexus here! The recording of the children screaming is horrifying, full stop. The recording is embedded in a story that doesn't offer much additional information, let alone “solutions.” Kids were being separated from their parents deliberately by the United States government, these children were in extreme distress, and were screaming as indifferent adults looked on. The information and emotion in that short story and audio clip was raw, but it created a popular outcry that changed national policy anyway.

Second, the immediate impact in this case did not negate the need for careful reporting and record creation. Thompson didn't stop asking questions and reporting after the executive order. Neither did other reporters. Caitlin Dickerson, another incredible reporter, published a thorough investigation of the people behind the family separation policy in the Atlantic. She meticulously documents the ways so many people, at so many levels of government, chose to execute this deliberately cruel policy. I'm not always (usually) a fan of long, retrospective investigations, but here I think Dickerson provides both valuable and actionable information, even though it came years after significant impact.

We now have documentation of the deliberate attempt to terrorize people looking to migrate to the United States or seek asylum here. We better understand how people who don't see themselves as deliberately cruel carried out such a policy anyway. We can understand that conditions that allowed for this policy remain and have generated equally cruel modern incarnations, as people are deported to foreign prisons without due process or are disappearing. Dickerson's reporting might not have a direct line to impact, but it still seems necessary and like it can continue to reverberate. I hope it can.

A decade-long wait for impact

Thompson's reporting created a tremendous impact within two days. Outlier reporter Koby Levin built on local reporting published almost eight years ago to return millions of dollars owed to Detroiters.

Outlier's has reported on the Wayne County Tax Auction since our founding in 2016. In the last 20 years, Wayne County has foreclosed on one in three Detroit properties at least once. This municipal catastrophe, caused in part by the city's overassessments of Detroit homes, is responsible for an almost wholesale redistribution of wealth within the city. Black homeowners lost, and real estate investors and speculators who bought up auctioned properties en masse gained.

Outlier's tax foreclosure reporting was primarily direct-to-resident. Detroiters could look up any property over a text message system to check foreclosure risk and the amount of tax debt. Anybody could then text or talk directly with a reporter. I know these texts helped hundreds of people save their homes from foreclosure. But the stories I wrote about the devastation caused by foreclosure did not seem to matter much.

Joel Kurth (a generous and great editor of mine when I freelanced) wrote a story on tax foreclosure in 2017 that did break through, in a way. He reported that Wayne County kept any excess proceeds it made when a home was sold at auction for more than the tax owed. The county funneled the hundreds of millions dollars it earned this way straight into its general fund. The tax auction continued, as did the practice of keeping excess proceeds. Two years later, however, a conservative legal practice based in California argued in front of the state supreme court that this practice was an unconstitutional taking. The lawyers cited Kurth's story as an authority, and the court ruled the practice unconstitutional.

It took five more years for the court and Legislature to compel counties to givet this money back to former homeowners. However, the county had no duty to proactively inform former property owners that they were owned money.

Instead, to claim their money, people had to somehow learn that money was owed to them, find an obscure and complicated form on the county website, figure out how to fill it out and get it notarized and sent in before the deadline. This is not accountability.

Outlier's Koby Levin, using foreclosure data made public by Alex Alsup, a data analyst and advocate in Detroit, stepped up. Levin organized mountains of data and hundreds of volunteers in an attempt to call and contact as many of the 2,400 people owed money as possible.

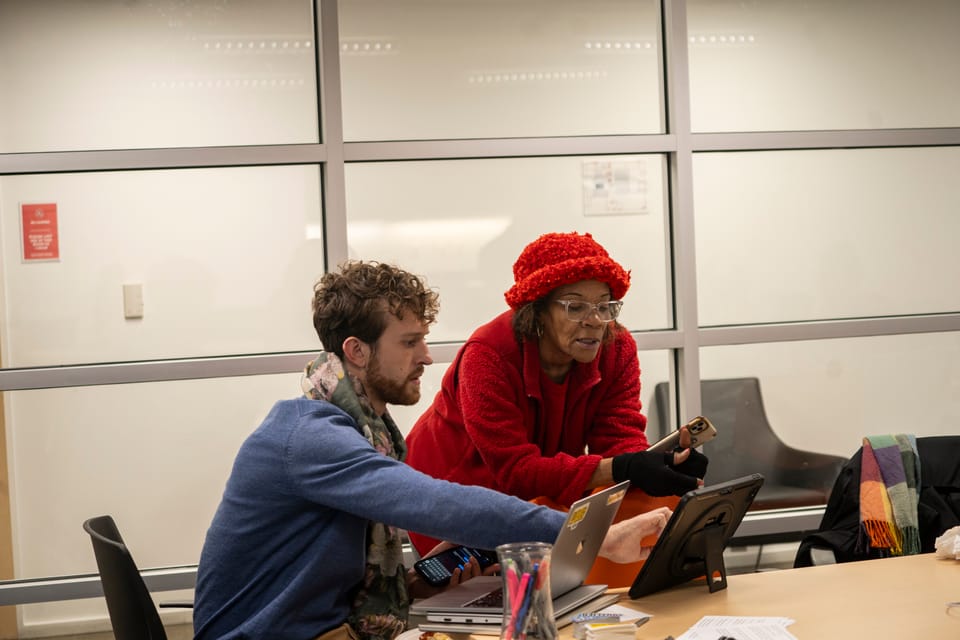

Levin, Detroit Documenters and project manager Shiva Shahmir spent months tracking down contact information, working with community partners, phone banking, sending text messages, and walking people through how to fill out their forms. Other newsrooms in Detroit jumped in to support the effort, especially WXYZ Channel 7. By the March deadline, this group had helped 481 people collectively owed almost $5.9 million to fill out forms.

This was an impact none of us could have predicted or planned for. It took a long time, a lot of collaboration and a lot of work. It doesn't make up for a home lost to foreclosure, but does create accountability and value. As to how it happened, Levin told Nieman Lab recently, “It would have felt like malpractice to have this information and not try to give it to people.”

It's alchemy, not science. If either of these stories help you to think about impact and value differently, I hope you'll tell me.

Take care until next time.