Inform me like I'm sick

I got the kind of phone call we all dread last week, as soon as I hit publish on my last post. I was still sitting at my desk, and watched a voice mail transcription from a call I thought was spam scroll down my phone.

My daughter was hospitalized, several states away, and it was serious. One week later, she is beginning to recover.

I won't be sharing more about her condition to respect her privacy. We so often feel entitled to other people's stories as reporters. Parents are even worse. Parents feel ownership over our children's stories because they feel like our stories, we just can't help it. But I've realized our only job is only to help her heal, not to tell her story.

I've not had much time for reflection here, but I've also not been able to ignore thinking about information. How to build information systems that can serve in a crisis is something I've long understood. I intuited it, I'm not sure from where. Because until now, I've not been inside of a crisis where I also needed to take in large amounts of complex information.

Information is such a valuable currency in medical settings and during a health crisis. Good doctors and nurses are experts in information provision, in addition to all the other things they need to master.

This experience has given me a different perspective on principles I've become attached to more recently and write about here; ideas like accompaniment and turning to medical decision-making frameworks for guidance in story structure.

I hope to write about these in more depth later, but here are two early lessons I've learned.

Accompaniment really is key: We already know how hard it is to take information on board during stress. The higher the stress, the more you need an actual person to interact with; a person who has shown you that they care.

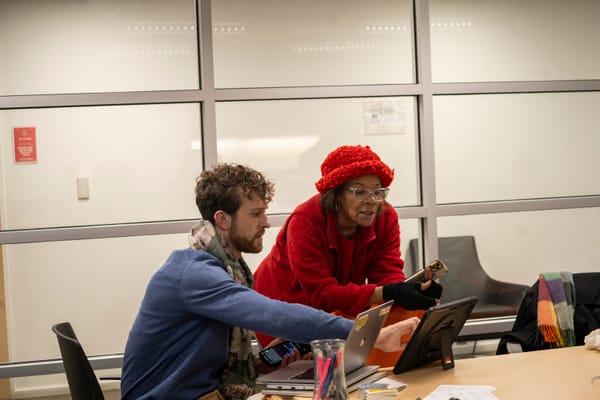

When we arrived here, somebody from my daughter's school met my husband and me at the hospital. She had designated herself as somebody who could accompany us. Her value was not in the information she could provide, she only had a little more than we did. Instead she helped us understand that we were not the only ones who cared about our daughter. My trust in her and the school increased exponentially, and my stress level decreased.

We can't accompany every member of our audience in person as reporters. I don't know what it looks like to accompany people outside of the text message system we use at Outlier. But there have to be more ways to do this at volume, and we need to find them. When the situation is difficult and the stakes are high, accompaniment matters for information uptake.

Don't overwhelm the consumer: The doctors and nurses we've spoken to over the last week have given us the information they think we need, and no more. We know their goal, which is our daughter's health, and that's our goal too. They answer our questions and are as responsive as they can be, but not all situations are information problems. When that's the case, less is more. I'm sure this feels like a power play to some patients or loved ones, but I've appreciated it.

I've long been interested in medical decision-making. A doctor's advice is useless if it is not followed, and the research around medical-decision making understands this. I've been looking at a recent review of more than 200 studies evaluating whether decision aids, short brochures, written treatment summaries, or videos, for example, help patients to make difficult decisions more than just speaking with a doctor would.

These aids do help, and I intend to dig in more later. But what I appreciate most right now about this work is the humility of it. The people who study patient decision-making come right out and admit there isn't one best care option most of the time. The professionals making these decision aids are trying to help patients make plans that are practical, align with their values and help them be "active, informed participants" in their care. This is yet another version of Darryl Holliday's "don't just engage, equip."

Doctors and nurses have figured out how to do help people who have to make high stakes decisions when they are sick be active and informed. We as journalists have more than a few lessons to learn from their work.

Take care of yourself until I write you again. If you have a medical professional in your life, thank them for all they do.