What do we owe those we misrepresent?

Know somebody else who needs respite from the attention economy or the doomscroll? Recommend they subscribe to Understated. Ideas on how to find, share and understand the information we need to stay engaged without being overwhelmed. Dispatches about once a week because that's plenty.

When I moved into my new office at Temple, I was thrilled about two things: a big window and about a dozen old magazines. I inherited a Fortune from 1946 and several LIFE issues from the 60’s onward with covers that range from surreal to iconic. First lady Nancy Reagan wearing denim on denim and “riding” a rocking horse is at one end of the spectrum. On the other is a flawless black-and-white shot of Marilyn Monroe.

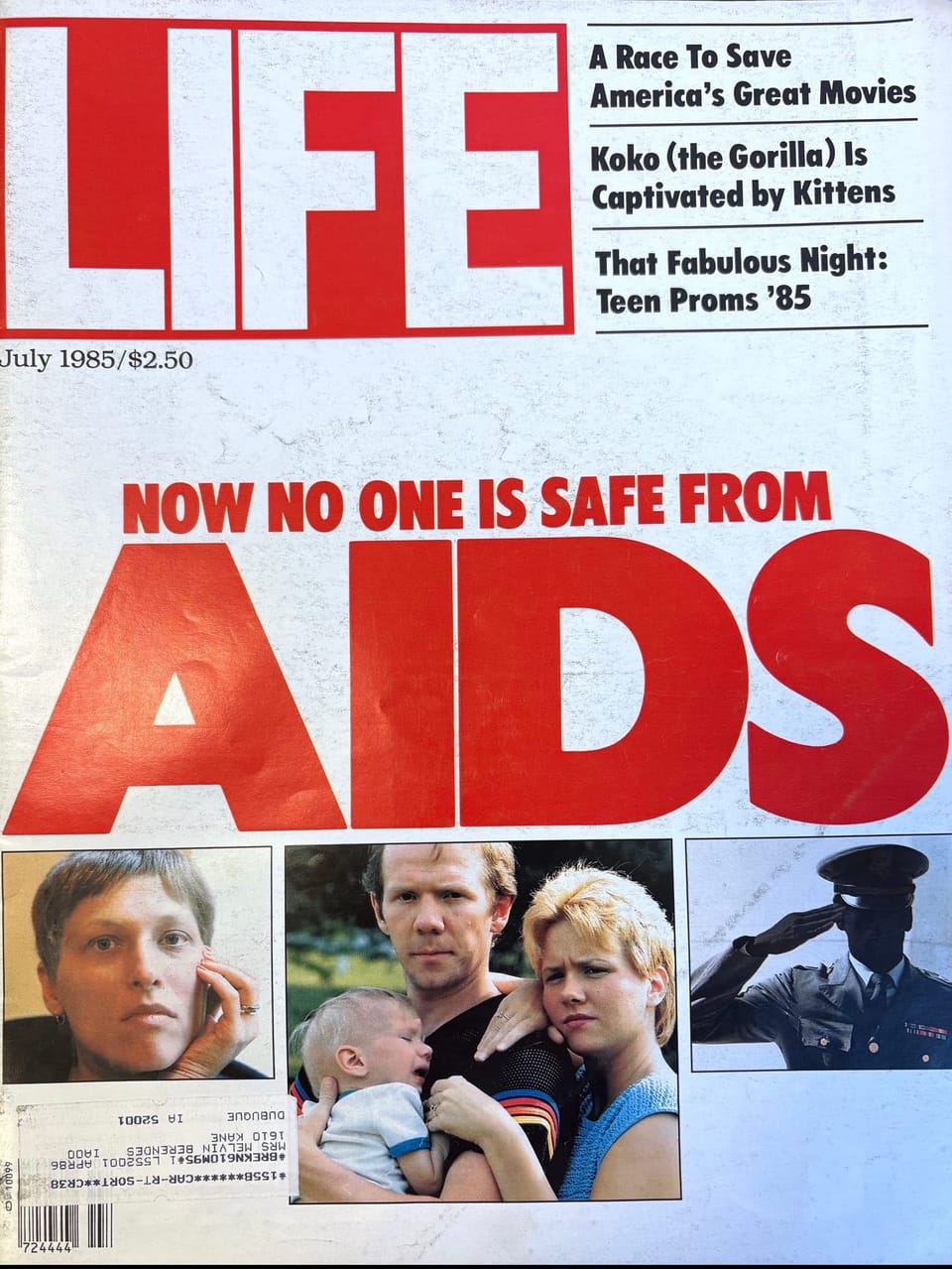

And then there is the July 1985 LIFE issue that proclaims, in all caps, “Now No One is Safe From AIDS.” I knew before I started reading it was unlikely to age well. It did not.

But what to do about pieces like this? It doesn’t get the facts wrong, exactly, but it is a particular and incomplete take positioned as truth. Should reporters and news organizations be trying to correct the record in cases like this? Should we take responsibility for our industry's mistakes if the people or publications aren't around when we have a more full understanding of the facts? What comes first, the reporting or the cultural change?

The current speed of publishing and the vitality of narratives make it feel more likely that reporters and news organizations will see, or make, the kind of framing mistakes that can perpetuate misunderstandings or cause harm.

The old LIFE story might have done both. It positions people who tested positive for HIV (I’m using the modern term here) as somehow distinct from a smaller group of people who were victims of the disease. The cover photos feature members of the smaller group: a young white family, a young white woman, and a Black male soldier in uniform with his face obscured.

The accompanying story mirrors the cover. HIV was not well understood by doctors, scientists, or journalists in 1985. The story doesn’t read as unsure of itself, though. Instead, it reflected and reinforced the prevailing idea that HIV had a moral dimension even post-transmission.

The reporters, Edward Barnes and Anne Hollister, present children, hemophiliacs, and heterosexual women (though not prostitutes) as having the most humanity. Sex workers and people living in poverty are interviewed but presented less fully and sympathetically. Gay men, who were disproportionately affected by HIV in 1985, barely get a mention, and none speak for themselves.

The reporters go to Belle Glade, FL, a small town in Palm Beach County (strange fact, the town is also featured in Edward R. Murrow’s famous Harvest of Shame broadcast from 1960). Belle Glade had the highest incidence of AIDS infections in the United States in 1985. The reasons were not understood by epidemiologists at the time but attributed in the story to prostitution, poverty, and migrant workers. And, even as HIV incidence was high, it was a small town. The number of people who tested positive for HIV between 1982 and 1986 was 62. Still, the reporters chose to write, “Belle Glade’s threat to other Americans, like that posed by homosexuals a few years ago, at first seems easy to dismiss.”

Officials and residents of Belle Glade said the stigma caused by the media attention in the 1980s had economic and social consequences. In a generous read of the past, it is possible these reporters and editors didn’t realize that their narrative choices presented a skewed story until years later. Do reporters and news organizations owe anything to people or to groups of people when this happens?

Some decide they do. This example of a Lexington, KY paper taking responsibility for not covering the entirety of the civil rights movement is kind of incredible. It also seems rare.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this kind of record correction. Have you seen examples where this is done well?

Do you consider this more meta record correction to be an essential function or news, or do you think it fits better under the umbrella of narrative shift? Would narrative shift work perhaps be more widely embraced if it explicitly tried to reframe our industry's past mistakes?

I have a suspicion news and information providers can make this kind of record creation less necessary by doing less of the editorial cherrypicking that was LIFE magazine's prerogative. When taste-making leads editorial decision-making, rather than filling information and accountability gaps, framing matters more. Reporters are far more likely to get framing, not facts, wrong.

I'm not fully decided but am leaning toward including record correction as an essential function, even as I have some reservations and unanswered questions about its utility. Record correction is likely to have low utility for individuals, but the social utility could be high. Are there elements of a correction you think are more likely to increase, or decrease, this social utility? Let me know. I'd love to hear from you.

Until next week, take care of yourselves.

What I'm reading

This toolkit about how communities view the value of local news and what kind of words they respond to best, commissioned by Press Forward. Don't focus on people not liking the word journalism! There's a lot in this report that is helpful and hopeful. People want news to be useful day-to-day. When it is, they value it and are willing to support it.

Dick Tofel's blog pre-gaming the Free Press acquisition by CBS. It seems like 150 million is a lot to pay for a startup with an estimated 170,000 paid subscribers, but this decision isn't really about the business. I agree with Dick that under Bari Weiss a lot more opinion is likely to be paraded as news, something nobody, truly nobody, actually needs.

Before I turn to the question of whether correcting the record-trying to reshape a collective understanding of what happened why given a better understanding of the facts and dynamics surrounding it-is an essential function of journalism I want to give an update on last weeks post.

I talked to Mattia Peretti and Jeremy Gilbert about their work on J3 (which they pointed out is not really an ongoing project but something they still care about) and we talked about the distinct tasks of increasing the utility of news and information for communities and the task of case making to news and information providers that they need to get on board.

I’ve always been involved in the first, just doing the work of trying to make local news more useful and now I’m doing a bit of both. Did you all see this report about what people respond to, and don’t, when it comes to how we talk about news and information? I think it’s hopeful.

We’re going to work on this case making even as we need more answers about what we can do to consistently provide utility.

If this is something you might want to get involved with let me know.

Record correction: here’s where the questions about individual utility and social utility can conflict. Because record correction is largely about bigger social impacts.

The process is important-and hard-what comes first? Consensus or reporting? How do you know what to go back to? Record correction is going to have low actual utility but the social utility can be high. How do we do this? Race, COVID,

https://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2032304_2032746_2033037,00.html

https://thewholestory.solutionsjournalism.org/complicating-the-narratives-b91ea06ddf63

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10871475/

https://www.readtangle.com/debunking-some-myths-about-tangle-and-me/

really interesting:

https://www.nytimes.com/2004/07/13/us/40-years-later-civil-rights-makes-page-one.html

https://dash.harvard.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/7312037d-c5af-6bd4-e053-0100007fdf3b/content

https://www.pressforward.news/wordsthatwork/

https://trustingnews.org/be-loud-about-mistakes-and-how-you-correct-them/

https://www.kentucky.com/latest-news/article210138324.html